Kenya’s blue economy was once described as a game changer that would open up thousands of jobs for the youth. Today, that vision is collapsing, leaving frustration and disappointment across the country. What was supposed to bring hope has instead turned into a story of delays, corruption claims, and false promises.

More than 50,000 potential jobs have already disappeared, and many young people who trained as seafarers or maritime professionals now feel stranded and betrayed.

The blue economy was promoted as a lifeline for young people facing high unemployment. Projects in shipping, fishing, and maritime training were highlighted as key areas of opportunity.

But years later, these projects remain stalled, with critics pointing fingers at government agencies accused of sabotaging deals and engaging in political wrangles instead of supporting real progress.

The big question many are now asking is why Kenya is turning its back on a sector that could change so many lives.

One of the major setbacks came when the government dissolved the advisory secretariat that was supposed to guide blue economy programs.

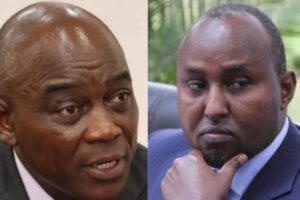

Former member Stanley Chai described the move as a blow that disrupted important work. Maritime analyst Andrew Mwangura also raised concern, saying the progress that had been achieved under retired General Samson Mwathethe now faces collapse.

Experts argue that interference and lack of independence have slowed down momentum, insisting that institutions like the Kenya Maritime Authority (KMA) and the Bandari Maritime Academy (BMA) should be allowed to operate without political pressure.

The issue of broken promises has made the situation worse. For years, the government told young seafarers to prepare for jobs abroad.

But many of those promises never materialized. At a recent BMA event supported by KMA, about 1,800 youths submitted their CVs. Later, it emerged that no real job offers existed. Critics said this amounted to misleading the youth and raising false hopes.

One of the biggest lost opportunities involved the Mediterranean Shipping Company (MSC), which had pledged to create 10,000 jobs for seafarers and provide 2,000 annual sea-time slots.

In exchange, MSC sought control of Terminal 2 at the port. Reports suggest that government officials blocked the deal in favor of rival company Maersk.

As a result, thousands of job opportunities slipped away. Another deal with an international maritime company that wanted to recruit 140 Kenyans from Middle Eastern hotels also collapsed after alleged sabotage by government offices, despite offering salaries as high as $3,000 for waiters.

In the middle of these frustrations, KMA has come under fire. Recently, it issued a directive tightening recruitment rules, stating that no recruitment can take place without a KMA license, licensed agents cannot charge seafarers, and monthly reports must be filed.

While this was meant to bring order to the sector, many see it as a delayed reaction to growing anger. One seafarer described the entire system as broken and outdated, accusing leaders of ignoring the youth.

Even though Wilhelmsen, a global maritime company, has launched a Nairobi office and offered some hope, this is a small light in a much darker reality.

For the thousands of Kenyan youths who were promised jobs, the promises remain empty. Kenya has the potential to become a major hub for maritime jobs, but corruption, bureaucracy, and political games continue to block progress.

Without decisive action, the dreams of many young Kenyans who trained to work at sea may never be realized.

Add Comment