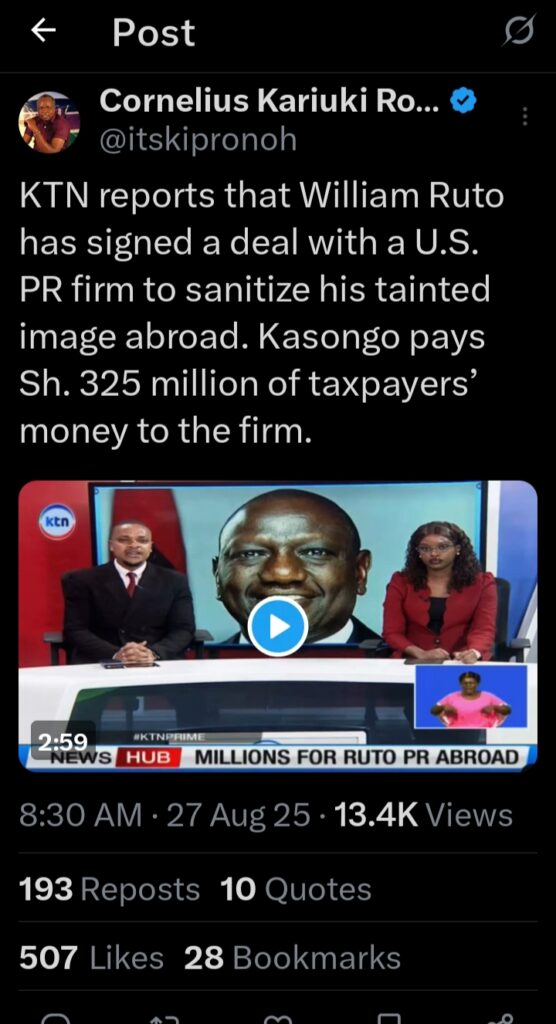

President William Ruto’s government has made a controversial move by signing a contract with a U.S.-based lobbying firm in a bid to strengthen its image in Washington.

The deal is with Continental Strategy LLC, a company linked to former U.S. Ambassador Carlos Trujillo, who previously served under Donald Trump.

According to reports, the contract was signed on August 6, 2025, and requires Kenya to pay about 27 million shillings every month.

This means taxpayers will shoulder an annual cost of more than 325 million shillings at a time when the country is already struggling with rising taxes, striking doctors, underfunded schools, and hospitals running short of basic supplies.

The main goal of the arrangement is to repair President Ruto’s reputation abroad, especially as U.S. lawmakers review Kenya’s major non-NATO ally status, which was granted by President Joe Biden in 2024.

The review is expected to take 90 days, and Congress is paying close attention to Kenya’s human rights record, including allegations of extrajudicial killings, abductions, and violent crackdowns on protests.

Concerns have also been raised over Kenya’s relationship with Sudan’s Rapid Support Forces, accused of war crimes, and its increasing ties with China, Russia, and Iran.

Continental Strategy is expected to push Kenya’s interests in Washington by organizing meetings, lobbying policymakers, and shaping public opinion to keep U.S. relations favorable.

The firm is not one of the traditional K Street giants but is well connected in Republican circles, having earned millions in lobbying revenue earlier this year.

For Ruto, the deal is part of a broader effort to maintain strong ties with the U.S., following his 2024 state visit that secured health and defense agreements worth billions.

However, his government’s decision has attracted sharp criticism at home. Many Kenyans argue that spending such vast sums on image building overseas ignores urgent problems at home.

The health sector is under strain, with doctors’ strikes drawing attention to drug shortages and delays in salary payments. Schools, too, are struggling due to late capitation funds, leaving many learners disadvantaged. Critics see the lobbying contract, which includes first-class travel and chauffeured services for the firm, as a symbol of misplaced priorities at a time when ordinary citizens face heavy economic pressures.

Ruto’s domestic image was already damaged by the 2024 protests against a finance bill that sought to raise taxes. The demonstrations turned violent, leading to accusations of excessive force by security agencies.

Though the bill was later withdrawn and the cabinet reshuffled, trust in the government remained shaken. In defending his leadership, Ruto has often pointed to economic pressures and international partnerships as necessary for growth, signing other deals such as a labor migration agreement with Germany and regional trade pacts under COMESA.

Still, the U.S. lobbying deal has sparked fears that taxpayers will be tied to long-term costs since the contract automatically renews unless terminated.

With shifting global alliances, some see the move as a way to win favor with a possible Trump comeback, complicating Kenya’s balancing act between the U.S. and China, one of its biggest investors.This is not the first time Kenya has turned to foreign lobbyists.

Previous administrations, including those of Daniel arap Moi and Uhuru Kenyatta, also hired firms to polish their image abroad. What makes the current move stand out is the timing, given the deep economic and social challenges facing the country. Public reaction on social media has been largely negative, with many demanding accountability and questioning why resources are being channeled abroad instead of fixing pressing local issues.

Add Comment