The unwritten political arrangement between President William Ruto and ODM leader Raila Odinga, built primarily on trust, has ignited discussions within a political environment marked by broken Memorandums of Understanding (MoUs).

Despite four of his key allies holding Cabinet positions, Odinga maintains that his ODM party has not entered into any formal alliance with Ruto’s UDA, reiterating that ODM remains in opposition.

This marks the second instance in recent years where Odinga has operated under such a trust-based agreement without any documented contract or official filing with the Office of the Registrar of Political Parties.

In the March 9, 2018 handshake between Odinga and then-President Uhuru Kenyatta, the Jubilee and ODM parties did not formalize their agreement until the lead-up to the 2022 General Election when they joined forces to establish the Azimio La Umoja One Kenya Coalition, endorsing Odinga as its presidential candidate.

The handshake, however, led to the Building Bridges Initiative reforms push, which ultimately failed to materialize.

In the past, political deals were typically formalized through signed agreements.

For example, when Odinga allied with KANU in 2002, he merged his National Development Party (NDP) with KANU and assumed the role of Secretary General.

Three NDP MPs, including Odinga, joined the Cabinet.

However, like other written deals, Odinga exited KANU ahead of the 2002 General Elections after President Moi endorsed Uhuru Kenyatta over him for the presidency.

Kenya’s political history is filled with broken promises and disregarded MoUs, leaving the effectiveness of unwritten “gentleman’s agreements” in question.

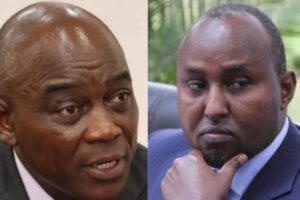

Kimilili MP Didmus Barasa criticizes written deals as political manipulation driven by coercion and mistrust, whereas gentleman’s agreements, he argues, are rooted in mutual understanding and shared interests.

According to Barasa, ODM’s support doesn’t necessitate legal backing.

Political analyst Prof. David Monda asserts that informal deals have become more viable than written MoUs due to the lack of commitment among political players to honor pre-election agreements.

He emphasizes that post-election dynamics often favor abandoning MoUs, disadvantaging smaller coalition partners.

This imbalance is evident in associations like the Raila-Kalonzo-Martha alliance.

In the run-up to the 2022 election, ANC leader Musalia Mudavadi and Ford Kenya leader Moses Wetangula secured key positions in the government through a deal with Ruto.

However, there’s an ongoing debate about whether their 30 percent share of government was fulfilled.

The situation is similar for Alfred Mutua’s Maendeleo Chap Chap and Moses Kuria’s Chama Cha Kazi, highlighting the fluidity and lack of legal enforcement in written agreements.

Kuria’s dismissal from the Cabinet and subsequent appointment to a State House role underscores this fluidity.

Kakamega Deputy Governor Ayub Savula notes that written MoUs, despite being filed with the registrar of parties, often hold no legal weight and are frequently disregarded after elections.

He suggests that these agreements are primarily tools for gaining political backing during campaigns, while the current arrangement with ODM is based more on trust and political goodwill.

Add Comment