The recent content circulating from the “nairobiloop” page has raised concern because of how it mirrors a classic pattern known as Domestic Amplification of a Foreign Information Manipulation Narrative, also referred to as FIMI-A.

The main issue here is not the debate around labour migration, nor is it whether the New York Times story exists.

The problem is how the narrative has been packaged, framed, and delivered to the Kenyan audience in a way that aligns closely with established foreign information manipulation techniques.

This makes it important to break down what exactly is happening and why it matters.

Domestic amplification means the story being pushed did not originate locally. The core narrative comes from abroad, and a local page simply repeats and reshapes it for a domestic audience.

In this case, the “nairobiloop” page functions as an amplifier, taking a foreign media report and adding its own layers of emotional framing and political targeting.

The end goal of such manipulation is rarely spontaneous public discussion. Instead, the target becomes political stability and public trust in institutions. When these two are weakened, external interests benefit quietly while citizens are left reacting to distorted narratives.

The first warning sign is the way the New York Times is used as a foundation of authority. The caption begins with the line “A New York Times investigation shows…”, which immediately positions the message as unquestionable truth simply because it is tied to a major international publication.

This is a familiar tactic in FIMI patterns. Foreign outlets often become launchpads for stories that are later picked up by actors who want to undermine local leadership or provoke public anger.

Even when the foreign report is factual, the way it is repackaged can change the intention behind it. Here, the emotional framing and selective emphasis show that the goal is not balanced discussion but agitation.

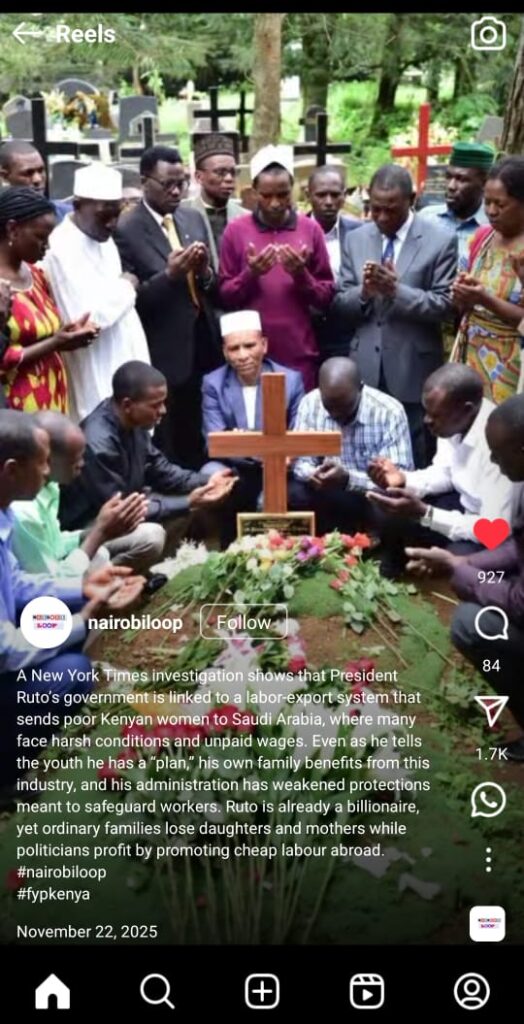

Another red flag is the image used in the post, which shows people crying at a grave. This visual does not illustrate the New York Times story, nor does it add factual clarity.

Instead, it is chosen to trigger deep emotional reactions. FIMI relies heavily on emotional hijacking because strong feelings reduce critical thinking.

By showing a burial site, grief, and death symbolism, the content is designed to direct anger and blame at the government and, more specifically, at the president.

This is not an informative choice; it is a manipulative one.

The narrative structure also aligns with well-documented propaganda lines that originate from rival networks in the Gulf region. The messaging focuses on claims about Kenyan women being exploited, protections being weakened, unpaid wages, and politicians profiting from labour migration.

While these topics are serious and deserve discussion, the specific combination and tone match patterns used in Gulf information wars where different countries attempt to weaken each other’s image by using labour migration as a pressure point.

When Kenyan platforms uncritically adopt this structure, the country becomes an unintended casualty in conflicts that have nothing to do with its internal reality.

The final and most concerning sign is how the narrative is crafted to erode trust. The reel claims that the president profits, that his family profits, that ordinary people suffer, and that Kenya is exporting women to die.

This messaging does not offer solutions, context, or accuracy. Instead, it pushes a direct attack on trust between citizens and their government. This erosion of trust is the central aim of foreign information manipulation. When people lose confidence in institutions, foreign actors who started the narrative gain an advantage.In the end, the issue here is not whether labour migration challenges exist.

The problem is the intentional design behind the narrative. The style, structure, and emotional engineering reveal a foreign-origin script repackaged by a local page for maximum domestic impact.

Understanding these patterns helps citizens stay alert and avoid becoming tools in someone else’s information strategy.

Add Comment