A five-year-old boy with a severe heart condition is now at the center of a painful test for Kenya’s healthcare system. His family had made all the arrangements for him to travel to India, where doctors were ready to perform a life-saving surgery that is not available in the country.

A generous donor had stepped in and covered the cost of flights, which amounted to about 1.9 million shillings, and the Social Health Authority had approved 500,000 shillings for the treatment.

Everything seemed in place until the Ministry of Health suddenly issued a directive freezing all approvals for overseas medical support.

Health Cabinet Secretary Aden Duale announced that this freeze would last 30 days, saying it was meant to review and align policies with new guidelines.

The family, already under heavy emotional and financial strain, was left devastated. They describe the government’s decision as showing insensitivity to urgent health needs, especially for children whose conditions can worsen quickly if treatment is delayed.

For them, time is running out, yet bureaucracy has shut the door. Their story reflects the struggles many Kenyans face as the country transitions from the old National Health Insurance Fund to the new Social Health Authority.

While the SHA was launched to improve universal health coverage and ensure efficiency, its early days have been marked by confusion, tough new rules, and disruptions to patients in critical need.

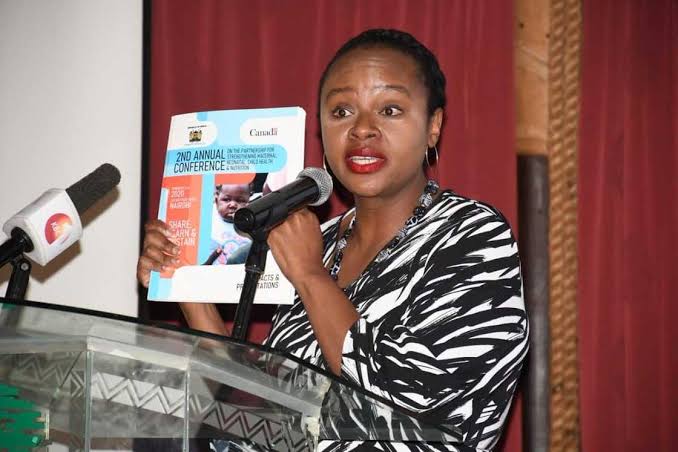

Dr. Mercy Mwangangi, who took over as CEO of the SHA in June 2025, has been tasked with strengthening local healthcare and reducing the dependence on foreign hospitals.

The authority has introduced strict measures requiring patients to provide up to 26 documents before approvals are granted, and only foreign hospitals contracted with the SHA will qualify for funding.

Officials argue these steps are necessary to prevent fraud and misuse of resources, pointing to recent cases where 40 hospitals were suspended over alleged irregularities. But for families like the boy’s, these reforms feel like punishment, trapping them in paperwork and delays while their loved ones suffer.

The government insists that the freeze is temporary and meant to create a stronger system. But for this child, every passing day brings more risk, from fatigue to possible heart failure.

Other patients share the same fate, with some stranded abroad after their support was cut mid-treatment.

Critics now question whether leaders like Dr. Mwangangi and institutions like the SHA truly understand the urgency of cases that cannot wait.

Kenya may be investing in building local capacity, but for children whose lives hang in the balance, the promise of future solutions means little without immediate help.

The case highlights the human cost of health reforms, reminding officials that policies must serve people, not the other way around.

Add Comment